Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe

Hier findest du eine exklusive Auswahl an hochwertigen Wetterschutzfarben der Marke Consolan. Diese Farben sind speziell dafür entwickelt worden, um Holz und andere Materialien vor den extremsten Wetterbedingungen zu schützen. Ob Regen, Schnee, Sonnenschein oder Frost – mit Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe bleibt die Schönheit und Struktur deiner Außenbereiche erhalten. Stöber durch unsere Auswahl und finde die perfekte Farbnuance für dein nächstes Projekt. Mit Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe kannst du sicher sein, dass deine Holzoberflächen nicht nur gut aussehen, sondern auch optimal geschützt sind.

Warum ist Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe so wichtig um Holz im Außenbereich zu schützen?

Wetterschutzfarbe ist bei Holz besonders wichtig, da Holz ein natürliches Material ist und daher anfälliger für Witterungseinflüsse als synthetische Materialien. Feuchtigkeit, Sonnenlicht und extreme Temperaturen können dazu führen, dass das Holz aufquillt, schrumpft, reißt, verzieht und schließlich verrottet. Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe schafft hier Abhilfe. Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe schützt das Holz vor Feuchtigkeit, indem die Farbe eine Barriere bildet, die verhindert, dass Feuchtigkeit in das Holz eindringt. Sie schützt das Holz auch vor UV-Strahlung und anderen Witterungseinflüssen, die dazu beitragen können, dass das Holz ausbleicht und seine Farbe verliert. Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe kann in manchen Fällen auch dazu beitragen, das Wachstum von Pilz- und Schimmelpilzsporen zu verhindern, die das Holz beschädigen und die Gesundheit beeinträchtigen können. Durch die Verwendung von Wetterschutzfarben kann die Lebensdauer des Holzes enorm verlängert werden.

Weshalb sind die Holzschutzfarben von Consolan so beliebt?

Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe wird seit Jahren auf Haltbarkeit überprüft. Die mit Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe gestrichenen Objekte bilden eine homogene Schicht, deren Filmeigenschaften auch nach langjähriger Belastung durch die Witterung nur sehr geringe Abnutzungserscheinungen aufweisen und somit dauerhaft intakt bleiben. Das Ergebnis der Prüfung: Renovierungsintervalle von mehr als 10 Jahren sind möglich. Die Lebensdauer des behandelten Holzes kann sich vervielfachen. Außerdem kann die Optik der Holzbauteile durch die große Farbauswahl unserer Holzschutzfarben verschönert werden. Hier noch weitere Vorteile von Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe auf einen Blick:

- Schutz vor Feuchtigkeit: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe bildet eine Barriere, die verhindert, dass Feuchtigkeit in das Holz eindringt. Dies hilft, das Aufquellen und Schrumpfen des Holzes zu verhindern und die Lebensdauer des Holzes zu verlängern.

- Schutz vor UV-Strahlung: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe schützt das Holz vor UV-Strahlung, die dazu beitragen kann, dass das Holz ausbleicht und seine Farbe verliert.

- Schutz vor Pilzen und Schimmelpilzen: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe kann das Wachstum von Pilz- und Schimmelpilzsporen verhindern, die das Holz beschädigen und die Gesundheit beeinträchtigen können.

- Schutz vor Vergrauen: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe kann das Vergrauen des Holzes verhindern und dazu beitragen, dass das Holz seine natürliche Farbe behält.

- Erhöhung der Widerstandsfähigkeit: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe erhöht die Widerstandsfähigkeit des Holzes gegenüber Witterungseinflüssen, insbesondere Regen, Schnee und starkem Wind.

- Erhöhung der Lebensdauer des Holzes: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe kann dazu beitragen, die Lebensdauer des Holzes zu verlängern.

- Verschönerung des Holzes: Consolan Wetterschutzfarben können auch dazu beitragen, das Aussehen des Holzes zu verbessern und es ansprechender zu gestalten.

In welchen Farben und Gebindegrößen kann ich Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe online kaufen?

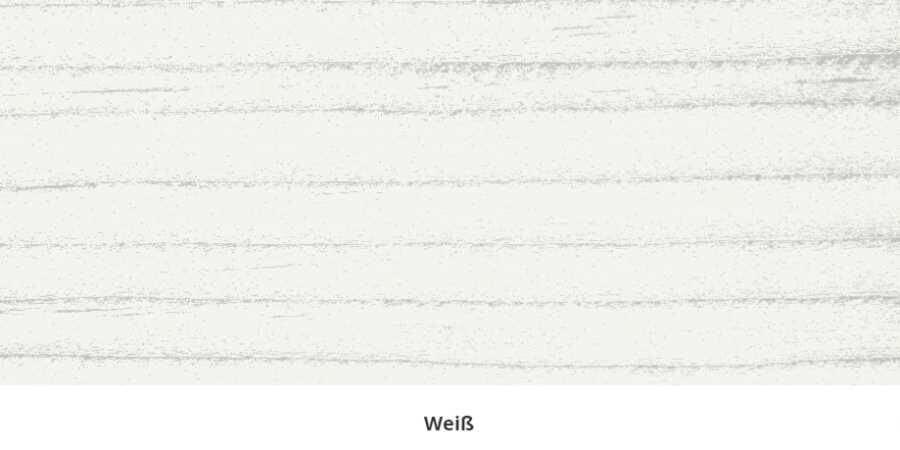

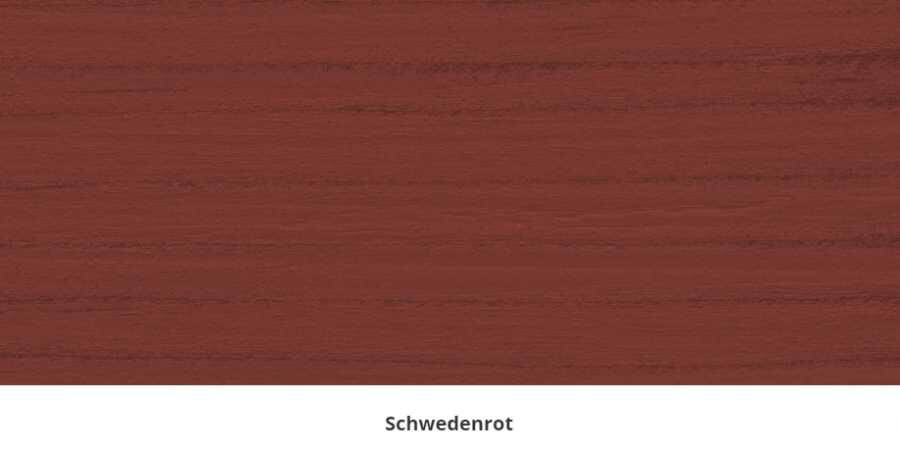

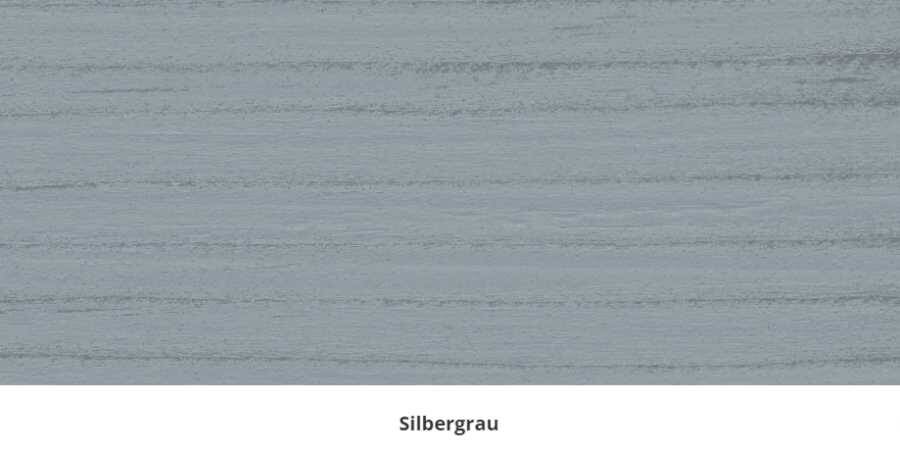

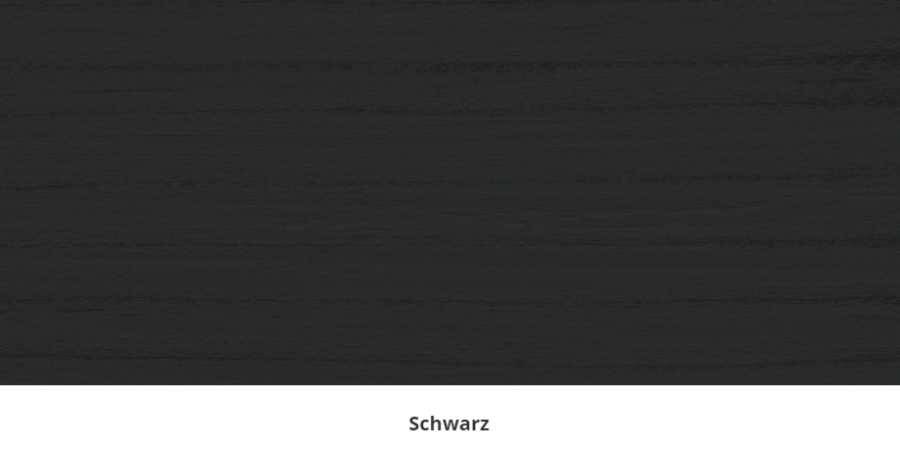

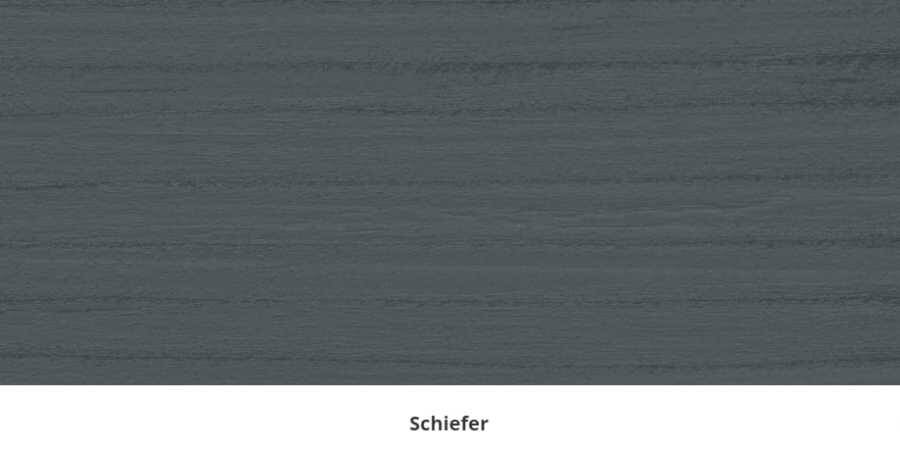

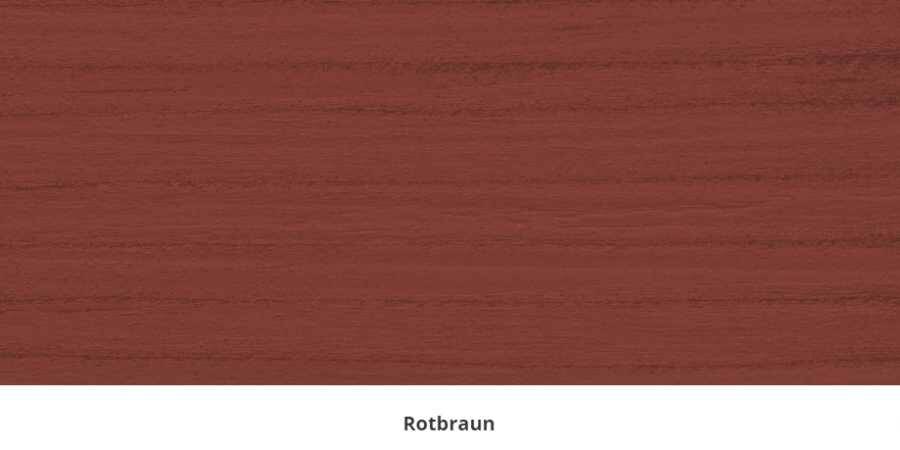

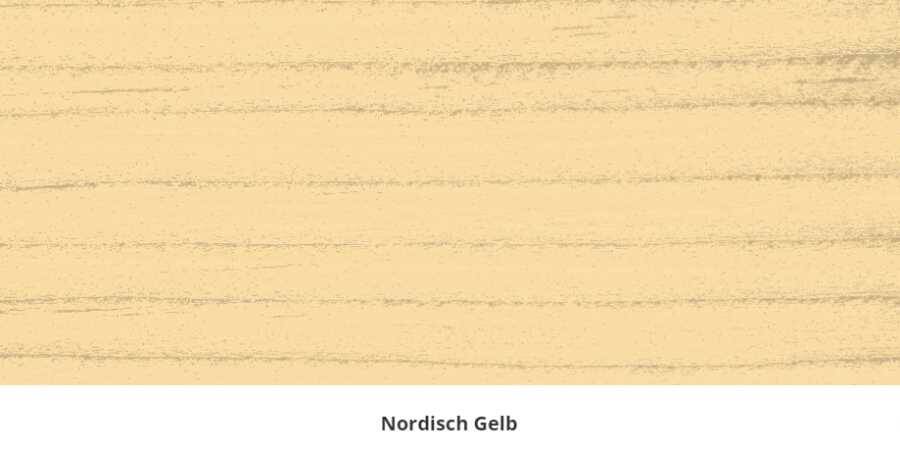

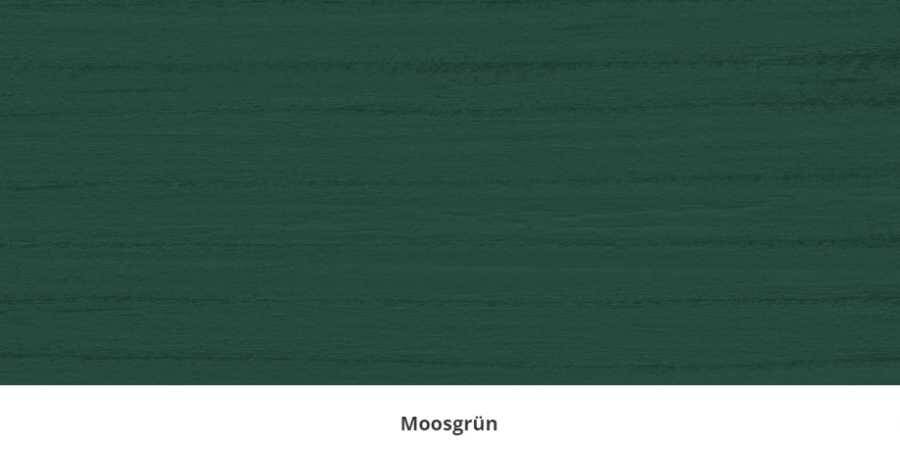

Die Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe ist bei uns in den Farbtönen Weiß, Dunkelbraun, Braun, Grün, Rotbraun, Schwarz, Grau, Gelb, Rot, Blau, Moosgrün, Taubenblau, Silbergrau, Schiefer, Schwedenrot und Nordisch Gelb und den Gebindegrößen 0,75 und 2,5 Liter erhältlich. Darüber hinaus sind die Farben Weiß, Dunkelbraun, Braun und Grün auch im 5 Liter Gebinde erhältlich. Holz ist ein Naturprodukt. Bitte beachte, dass jede Holzart die Farbe anders aufnimmt. Die Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe vereint effektiven Schutz vor Nässe, Verwitterung und UV-Strahlung mit einem hochdeckenden Anstrich in wundervollen Farbtönen, die seidenglänzende Oberflächen hinterlassen. Diese Holzschutzfarbe bietet bis zu 10 Jahre optimalen Wetterschutz, ist farbtonbeständig, geruchsmild und nach Trocknung komplett geruchlos.

Woher weiß ich eigentlich, wie viel Farbe ich brauche?

Um herauszufinden, wie viel Farbe du für dein Projekt benötigst, solltest du zunächst die Fläche berechnen, die gestrichen werden soll. Du kannst dies tun, indem du die Länge und die Breite der Oberfläche misst und diese Werte multiplizierst. Wenn du die Fläche in Quadratmetern kennst, kannst du die empfohlene Anstrichmenge auf der Verpackung der Farbe überprüfen, um die Menge an Farbe zu berechnen, die du benötigst. Die empfohlene Anstrichmenge variiert je nach Farbtyp und -hersteller, aber sie liegt in der Regel zwischen 8 und 12 Quadratmeter pro Liter.

Es ist wichtig zu beachten, dass der Anstrichbedarf von verschiedenen Faktoren beeinflusst werden kann, wie z.B. der Art des Untergrundes, der Porosität des Untergrundes, der Anzahl der Schichten, die aufgetragen werden sollen, und dem Zustand des Untergrundes vor dem Anstrich. Es ist immer empfehlenswert, ein wenig mehr Farbe als die berechnete Menge zu kaufen, um sicherzustellen, dass du genug hast, falls es notwendig ist, eine zusätzliche Schicht aufzutragen oder um Farbunterschiede auszugleichen.

Wie viel Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe du für dein Projekt ungefähr benötigst, kannst du dir übrigens auch ganz unkompliziert in unserem nachfolgenden Bedarfsrechner ermitteln lassen. Im Folgenden findest du:

- Eine bebilderte Anleitung zur Produktanwendung unserer Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe

- Eine Farbübersicht der Consolan Wetterschutzfarben

- Unseren Bedarfsrechner für Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe

So geht - Produktanwendung von Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe:

Holz ist ein beliebter Werkstoff im Garten, denn das natürliche Material betont die Nähe zur Natur und strahlt Gemütlichkeit aus. Mit der Zeit hinterlassen jedoch Temperaturschwankungen, Feuchtigkeit und Sonneneinstrahlung sichtbare Spuren. Holz benötigt deshalb in regelmäßigen Abständen Pflege, um den Wetterschutz aufrecht zu erhalten. Wenn Du Holz richtig vorbehandelst und mit der elastischen und atmungsaktiven Wetterschutzfarbe von Consolan streichst, ist ein Neuanstrich erst nach bis zu zehn Jahren wieder nötig. Und so geht es: Als Vorbereitung den Arbeitsplatz mit Folie oder Papier abdecken. Entferne dickschichtige, abgeplatzte oder nicht tragfähige Altanstriche. Achtung: Die Weiterbehandlung wie Schleifen, Abbrennen etc. von Farbschichten kann gefährlichen Staub und/oder Rauch entwickeln. Angemessene (Atem-)Schutzausrüstung anlegen, falls erforderlich. Bürste Staub und Schmutz ab. Material gut umrühren und mit weichem Flachpinsel oder Farbroller zügig verarbeiten.

Anwendung auf altem bzw. neuem Holz

- Neues Holz: benötigt keine Vorbehandlung (Ausnahme: Lärchenholz; siehe techn. Merkblatt weiter unten)

- Altes Holz: Gut haftende Altanstriche können überstrichen werden. Lacke, abplatzende, rissige oder nicht tragfähige Altanstriche vorher entfernen! Verschiedene Untergründe verlangen verschiedene Vorbereitungen und einen teilweise anderen Anstrichaufbau. Siehe hierzu im technischen Merkblatt unter Anstrichaufbau!

Unser Bedarfsrechner zur Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe:

Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe - Bedarf berechnen

Meine Fläche:

Breite: cm

Höhe: cm

Fläche: m²

Ergebnis: Du brauchst ca. Liter, bei zwei Anstrichen.

Diesen Bedarf deckst du mit Dose/n zu je 750 ml.

Was musst du bei der Verwendung von Consolan Wetterschutzfarben beachten?

Holz ist ein beliebter Werkstoff im Garten, denn das natürliche Material betont die Nähe zur Natur und strahlt Gemütlichkeit aus. Mit der Zeit hinterlassen jedoch Temperaturschwankungen, Feuchtigkeit und Sonneneinstrahlung sichtbare Spuren. Holz benötigt deshalb in regelmäßigen Abständen Pflege, um den Wetterschutz aufrechtzuerhalten. Wenn du das Holz richtig vorbehandelst, ist ein Neuanstrich erst nach bis zu zehn Jahren wieder nötig. Und so machst du es: Als Vorbereitung decke deinen Arbeitsplatz mit Folie oder Papier ab. Entferne dickschichtige, abgeplatzte oder nicht tragfähige Altanstriche. Achtung: Die Weiterbehandlung wie Schleifen, Abbrennen etc. von Farbschichten kann gefährlichen Staub und/oder Rauch entwickeln. Lege angemessene (Atem-)Schutzausrüstung an, falls erforderlich. Bürste Staub und Schmutz ab. Rühre das Material gut um und verarbeite es zügig mit einem weichen Flachpinsel oder Farbroller.

Die Verarbeitungshinweise des Herstellers sowie Informationen aus dem technischen Merkblatt und Sicherheitsdatenblatt solltest du auf keinen Fall missachten. Bitte lies auch die Produktbeschreibungen und Hinweise auf der Farbdose gründlich, damit ein optimales Ergebnis erzielt wird. Ganz allgemein gesprochen lässt sich folgendes zur Verwendung von Wetterschutzfarben sagen:

- Untergrundvorbereitung: Der Untergrund sollte sauber, trocken und frei von Schmutz, Fett, Algen und Pilzen sein, bevor du die Consolan Holzschutzfarbe aufträgst. Es empfiehlt sich auch, den Untergrund zu schleifen, um eine bessere Haftung der Farbe zu erreichen.

- Wetterbedingungen: Consolan Wetterschutzfarben sollten bei trockenem Wetter und möglichst bei Temperaturen zwischen 10 und 25 Grad Celsius aufgetragen werden. Es ist wichtig darauf zu achten, dass es nicht regnet oder die Feuchtigkeit im Untergrund zu hoch ist, da dies die Trocknung der Farbe verlangsamen und die Haftung beeinträchtigen kann.

- Schichtdicke: Verwende die empfohlene Schichtdicke, die auf der Verpackung angegeben ist, um sicherzustellen, dass die Farbe die gewünschte Wirkung hat.

- Trocknungszeit: Lass die Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe vollständig trocknen, bevor du eine weitere Schicht aufträgst oder Gegenstände auf der gestrichenen Oberfläche platzierst.

- Sicherheitsmaßnahmen: Verwende Schutzhandschuhe und Atemschutz, wenn du Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe verarbeitest und sorge für ausreichende Belüftung, um den Kontakt mit Farbdämpfen zu vermeiden.

- Materialien: Verwende Pinsel, Rolle oder Sprühgerät für die Farbe, um eine gleichmäßige Verteilung und ein besseres Ergebnis zu erzielen.

- Farbmischung: Mische die Farbe gründlich, bevor du sie verwendest, um sicherzustellen, dass die Farbe einheitlich ist.

- Farbaufbewahrung: Bewahre die Farbe in einem geschlossenen Behälter auf und verwende sie innerhalb der angegebenen Verfallsdaten, um ein optimales Ergebnis zu erzielen.

Tipps und Erfahrungsberichte unserer Kunden zur Anwendung von Wetterschutzfarben:

- Holz vorbehandeln: Behandle das Holz vor dem Streichen mit einem Holzschutzmittel, um Pilz- und Insektenbefall zu verhindern und die Lebensdauer der Farbe zu verlängern.

- Verwende den richtigen Pinsel: Nutze einen Pinsel mit natürlichen Borsten, um ein besseres Ergebnis zu erzielen. Vermeide synthetische Pinsel, da diese die Farbe nicht so gut aufnehmen und verteilen können.

- Streichrichtung beachten: Streiche in der Richtung der Maserung, um ein besseres Ergebnis zu erzielen und die Farbe gleichmäßig aufzutragen.

- Mehrschichtig arbeiten: Trage mehrere dünne Schichten auf, anstatt eine dicke Schicht. Dies ermöglicht eine bessere Haftung und eine gleichmäßigere Oberfläche.

- Trocknungszeit beachten: Lass jede Schicht vollständig trocknen, bevor du die nächste Schicht aufträgst.

- Farbe testen: In vielen Fällen sehen die Holzschutzfarben und Holzlasuren in der Dose und vor der Trocknung anders aus, als im fertigen Zustand. Teste deine Wunschfarben also vorab an einem kleinen Stück Holz, damit das Ergebnis am Ende auch garantiert deinen Vorstellungen entspricht.

- Unbedingt beachten: Farbabweichungen zwischen Abbildung und Original sind möglich und variieren je nach Lichtverhältnissen und den Farb- und Helligkeitseinstellungen deines Bildschirms.

- Vorausdenken: Holz ist ein Naturprodukt. Unterschiedliche Holzarten nehmen die Holzfarbe bzw. Holzlasur unterschiedlich auf. Je nach Holzart, Ton und Maserung kann ein und dieselbe Holzschutzfarbe ein unterschiedliches Endergebnis erzielen.

Wann solltest du eine Grundierung verwenden?

Es ist grundsätzlich empfehlenswert, eine Consolan Grundierung aufzutragen, bevor du Consolan Holzschutzfarbe aufträgst. Die Grundierung hilft dabei, das Holz vor Feuchtigkeit und Schädlingen zu schützen und sorgt dafür, dass die Farbe besser haftet und länger hält. Außerdem verbessert es das Farbbild. Stelle sicher, dass du die passende Grundierung zur Farbe verwendest und dass das Holz sauber und trocken ist, bevor du die Grundierung aufträgst. Bei Consolan Holzschutzfarbe solltest du entweder Consolan Isoliergrund (für helle Farbtöne) oder Consolan Holzgrund verwenden (dunkle Farbtöne). Eine Grundierung hat mehrere Vorteile, wenn sie auf Holz aufgetragen wird:

- Schutz vor Feuchtigkeit: Eine Grundierung hilft dabei, das Holz vor Feuchtigkeit und Witterungseinflüssen zu schützen, indem sie eine Barriere zwischen dem Holz und den Elementen bildet.

- Haftvermögen verbessern: Eine Grundierung verbessert die Haftung der Farbe auf dem Holz, was dazu beiträgt, dass die Farbe länger hält und weniger häufig erneuert werden muss.

- Ebenmäßige Farbauftragung: Eine Grundierung glättet die Oberfläche des Holzes und sorgt für eine ebenmäßige Farbauftragung.

- Verhinderung von Verfärbungen: Eine Grundierung kann dazu beitragen, dass das Holz nicht verfärbt und die Farbe länger frisch aussieht.

- Schutz vor Insekten und Pilz: Einige Grundierungen enthalten Insektizide und Fungizide, die das Holz vor Insekten und Pilz schützen können.

Es ist wichtig zu beachten, dass die Wahl der richtigen Grundierung für das jeweilige Holz von großer Bedeutung ist, um die bestmöglichen Ergebnisse zu erzielen.

Stimmt es, dass Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe auch für Zinkblech geeignet ist?

Ja, die spezielle Wetterschutzfarbe von Consolan, die neben Holz auch für Zinkblech geeignet ist, bringt diesen Vorteil mit sich. Die Consolan Wetterschutzfarben schützen das Zinkblech vor Korrosion und anderen Schäden durch Witterungseinflüsse. Sie bilden eine Barriere gegen Feuchtigkeit und andere Umwelteinflüsse, die das Zinkblech angreifen können. Wetterschutzfarben für Zinkblech sind in der Regel langlebig und lassen sich leicht auftragen. Es ist wichtig, die Anweisungen des Herstellers (Consolan) sorgfältig zu lesen und die empfohlene Schichtdicke und Trocknungszeit einzuhalten, um ein optimales Ergebnis zu erzielen. Grundsätzlich spricht aber nichts dagegen, auch deinen Zink Dachrinnen und Zink Regenrohren eine tolle neue Farbe zu geben.

Was ist denn der Unterschied zwischen Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe und einer Lasur?

Consolan Holzschutzfarbe und Xyladecor Holzlasur sind Produkte, die verwendet werden, um Holz im Freien zu schützen und zu gestalten, aber sie haben einige wichtige Unterschiede. Wetterschutzfarbe ist ein Produkt, das aufgetragen wird, um die Optik und den Schutz von Oberflächen zu verbessern. Es besteht normalerweise aus Pigmenten, Bindemitteln und Lösungsmitteln und bildet eine dichte, deckende Schicht auf der Oberfläche. Holzlasur hingegen ist ein Produkt, das aufgetragen wird, um die natürliche Schönheit von Holz zu betonen und gleichzeitig vor Witterungseinflüssen und Abnutzung zu schützen. Es besteht aus Lösungsmitteln, Pigmenten und Bindemitteln und bildet eine dünnere Schicht als Holzschutzfarbe. Holzlasur ermöglicht es dem Holz, atmen zu können und erhält die natürliche Maserung des Holzes. Eine Xyladecor Holzlasur dringt sehr tief in das Holz ein und kann im Verbrauch daher je nach Saugfähigkeit des Holzes stark variieren. Ein weiterer Unterschied ist, dass Holzschutzfarbe die Optik des Holz vollständig verändern kann, während Lasur die natürliche Farbe des Untergrundes hervorhebt und sie durchscheinen lässt.

Zertifiziert nach DIN EN 927-2

Die Norm DIN EN 927-2 bietet einen international anerkannten Standard, der ursprünglich für die besonderen Herausforderungen von Industriebeschichtungen entwickelt wurde. Unter realitätsnahen Bedingungen werden Freibewitterungstests durchgeführt. Folgender Versuchsaufbau war für Consolan vorgegeben: Imprägnierung Consolan Bläueschutz wässrig, Grundierung Consolan Isoliergrund Weiß, deckender Anstrich zweimal Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe. Zur Sicherheit wurden gleich mehrere Farbtöne auf Eignung geprüft. Für die Tests wurden Kiefersplintholzplatten beschichtet und auf Bewitterungsgestellen natürlich bewittert. Dadurch wurden die Probeplatten intensiv Regen, Sonne und Frost ausgesetzt. Nach Ablauf des Testzeitraums nahmen die Prüfer die Proben im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes unter die Lupe. Die Anstrichfilme wurden auf Risse, Blasen, Abblätterungen und Schimmelbildung untersucht. Des Weiteren wurde mit der Gitterschnittmethode die Haftfestigkeit getestet. Das Ergebnis des Härtetests: Consolan bestand die Testkriterien ohne Beanstandungen. Consolan bietet somit sicheren Schutz für Holzbauteile im Außenbereich. EN 927-2 befasst sich mit diesen Themen und legt eine begrenzte Anzahl an zwingend erforderlichen Leistungskriterien fest sowie freiwillige Prüfungen, die auf genormter Grundlage Zusatzinformationen liefern können. Für diese Norm ist das DIN-Gremium NA 002-00-15 AA "Bautenbeschichtungen" zuständig.

Technisches Merkblatt und Sicherheitsdatenblatt zur Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe

Alle Details zur Anwendung / Verarbeitung und den Eigenschaften der Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe findest du noch mal im: 'Technischen Merkblatt Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe'. (gültig für alle Farbtöne)

Alle Informationen zur Zusammensetzung, möglichen Gefahren und zur Sicherheit findest du im: 'Sicherheitsdatenblatt Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe'. (gültig für alle Farbtöne)

FAQ - Häufige Fragen zur Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe, die immer wieder auftauchen:

Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe ist in erster Linie für den Pinselauftrag konzipiert. Das Auftragen mit einem Pinsel ermöglicht eine gründliche Durchdringung des Holzes und sorgt für einen optimalen Schutz.

Wenn Sie jedoch dennoch überlegen, die Farbe zu spritzen, sollten Sie einige Dinge beachten: Die Wetterschutzfarbe wird in der Regel zu dickflüssig sein, um direkt gespritzt zu werden. Sie könnten in Erwägung ziehen, die Farbe gemäß den Herstellerangaben zu verdünnen, um die richtige Konsistenz für das Spritzen zu erreichen. Spritzgerät: Stellen Sie sicher, dass Sie ein geeignetes Spritzgerät verwenden, das für dickflüssige Farben geeignet ist.

Kunden haben uns berichtet, dass beim Spritzen das Ergebnis ungleichmäßig und fleckig werden kann.

Nacharbeit: Nach dem Spritzen kann es hilfreich oder notwendig sein, mit einem Pinsel über die Oberfläche zu gehen, um sicherzustellen, dass die Farbe gleichmäßig verteilt ist und in das Holz eindringt. Daher besser gleich mit einem Pinsel auftragen!

Die Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe Holzschutz außen von Consolan ist unser Profi Tip. Die Schutzfarbe ist nicht nur hochdeckend und sehr ergiebig, sie ist auch praktisch geruchslos, elastisch und vom Hersteller aus für bis zu 10 Jahre wetterfest! Sie gilt als Profi Produkt im Bereich Wetterschutzfarben für Hölzer im Außenbereich. Damit kannst du nichts falsch machen.

Für die Außenflächen von Fenstern ist diese Wetterschutzfarbe gut geeignet. Für die Innenflächen von Fenstern ist sie nicht zu empfehlen, weil sie schmutzanfälliger ist als Kunstharzlack. Auch in den Fensterfalzen solltest du besser mit Kunstharzlack arbeiten, weil der Anstrich mit Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe aufgrund der hohen Elastizität bei Temperatur- und Druckeinwirkung zum Nachkleben neigt. Für Fenster empfielt sich zum Beispiel unser Dulux Fensterlack Venti.

Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe eignet sich auch für die Anwendung auf Zink und verzinktem Stahl. Für Holzfußböden oder Schwimmbecken ist das Produkt nicht geeignet, da der Anstrich für mechanische Belastung nicht hart genug ist. Auch auf Kunststoff solltest du die Wetterschutzfarbe nicht verwenden, weil sie auf diesem Material keine ausreichende Haftung hat.

Für Möbel und andere mechanisch beanspruchte Oberflächen ist die Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe nicht geeignet. Da sie einen dauerelastischen Film bildet, kann es bei mechanischer Beanspruchung zu einer Abfärbung von Pigmenten kommen.

Ja, alle Farbtöne der Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe kann man untereinander mischen, so entstehen ganz individuelle Farbvarianten. Die Farbtöne sind auch mit Wasser misch- / verdünnbar. Der Hersteller empfielt allerdings mit nicht mehr als max. 10% Wasser zu verdünnen.

Ja, alle Farbtöne der Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe sind auch mit Wasser misch- / verdünnbar. Der Hersteller empfielt allerdings mit nicht mehr als max. 10% Wasser zu verdünnen.

Natürlich bei uns! Im Erhard-Shop.de, dem Webshop der Erhard-Trading GmbH. Wir sind Consolan Fachhändler und für unsere guten Preise, die hohe Verfügbarkeit und den schnellen Versand bekannt. Kaufen Sie Consolan Wetterschutzfarbei einfach direkt hier in unserem Onlineshop!

Häufige Problem bei der Verwendung von Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe, die uns regelmäßig erreichen:

Ursache: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe ist ein dauerelastisches Material. Klebebänder müssen daher sofort entfernt werden bzw. solange der Anstrich noch nass ist.

Lösung: Unter der Voraussetzung, dass der Untergrund sauber und tragfähig ist, klebe die Fläche erneut ab, wiederhole den Anstrich und entferne das Klebeband sofort danach.

Ursache: Auch auf dem Gebinde von Consolan Wetterschutz-Farbe wird darauf hingewiesen, dass sie nicht auf Borsalz-imprägnierten Hölzern verarbeitet werden kann.

Lösung: Kesseldruckimprägnierte Hölzer (Imprägnierung mit Borsalz) sollten vor einem deckenden Anstrich auf jeden Fall 3 bis 6 Monate abwittern, damit ein filmbildender Anstrich problemlos haftet.

Ursache: Consolan Wetterschutz-Farbe ist in erster Linie ein Produkt für den Außenbereich. Ein spezielles Bindemittel, das nicht voll aushärtet, verursacht in geschlossenen Räumen eine Geruchsbelästigung.

Lösung: Schleif den Anstrich leicht an und trage danach einen Acryl-Lack auf.

Ursache: Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe ist ein dauerelastischer Dispersionslack, der thermoplastisch reagiert, um die Holzbewegungen mitzumachen. Er ist für mechanisch beanspruchte Flächen ungeeignet.

Lösung: Abhilfe schaffst du durch Überlackieren.

Ursache: Die Verfärbungen stammen nicht von der Wetterschutzfarbe, sondern von wasserlöslichen Holzinhaltsstoffen, die durch die Farbe durchdiffundieren.

Lösung: Die Schnittholzkanten müssen völlig zugestrichen werden. Den Sockel kannst du mit einem Hochdruckreiniger säubern und bei starken Verschmutzungen nachstreichen.

Ursache: Die Verfärbung entsteht durch die Holzinhaltsstoffe, die wasserlöslich sind und durch den Anstrichfilm hindurchdiffundieren.

Lösung: Um das Problem zu beheben, ist ein dreifacher Anstrich mit Consolan Isoliergrund Weiß erforderlich.

Ursache: Hier liegt Korrosion (Rostbildung) durch winzige Metallsplitter der Stahlwolle vor.

Lösung: Schleif das Garagentor mit einem metallfreien Schleifmittel gründlich an, und streiche es anschließend zweimal mit einem lösemittelhaltigen Alkydharzlack.

Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe online kaufen

Du suchst einen Online-Shop, in dem du Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe online kaufen kannst? Dann bist du bei uns genau richtig! Unser Onlineshop bietet dir eine tolle Auswahl an verschiedenen Artikeln aus diesem Bereich, sowie umfangreiches Zubehör. Wir haben alles, was du für deine Anforderungen und dein Projekt suchst.

Kaufe angenehm von zu Hause aus ein und lass dir die Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe direkt nach Hause liefern. In unserem langjährig etablierten Shop mit unserer einfachen Navigation findest du schnell das Richtige. Auch Wetterschutzfarbe und Holzlasur für deine Anforderungen. Unser Onlineshop bietet dir auch die Möglichkeit, Wetterschutzfarbe und Holzlasur nach Marke zu filtern oder verschiedene Wetterschutzfarbe und Holzlasur miteinander zu vergleichen, sodass du schnell das Richtige findest.

Neben einer großen Auswahl an vielen verschiedenen Produkten, wie auch Wetterschutzfarbe und Holzlasur, bieten wir auch einen hervorragenden Kundenservice. Unser Team steht dir gerne zur Verfügung, falls du Fragen zu unseren Produkten hast oder Hilfe bei der Auswahl benötigst. Wir sind bekannt für unsere schnelle Lieferzeit und einen reibungslosen Bestellprozess.

Warum wir der Onlineshop für Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe sind?

Vertraue auf die perfekte Sortimentsauswahl, die wir anbieten und kaufe Wetterschutzfarbe und Holzlasur online bei uns. Wir haben alles, was du brauchst. Bestelle noch heute und genieße vielfältige Zahlungsmöglichkeiten mit schneller Lieferung in unserem Onlineshop.

Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe und Xyladecor Holzlasur sind bei uns zu einem budgetfreundlichen Preis erhältlich und werden schnell geliefert. Wir bieten auch flexible Zahlungsoptionen, damit du deine Bestellung schnell und einfach abschließen kannst. Wenn du auf der Suche nach einer sicheren und zuverlässigen Möglichkeit bist, Wetterschutzfarbe und Holzlasur online zu kaufen, dann bist du bei uns genau richtig.

Zögere nicht, uns zu kontaktieren, falls du noch Hilfe brauchst oder weitere Informationen benötigst. Wir freuen uns darauf, dir helfen zu können und dir die bestmögliche Erfahrung beim Kauf von Consolan Wetterschutzfarbe und Xyladecor Holzlasur in unserem Onlineshop zu bieten. In unserem Onlineshop kannst du die Wetterschutzfarben von Consolan günstig und einfach online bestellen.